This is a story that Beulah Buckner got a hint about many years ago when she was researching for a book she planned to write about early Black life in Howard County, but didn’t get to finish before she passed away in 2005. As seeds tend to do with a little water and light upon them, it grew when it was found recently and nurtured into what you will read below. What follows is a story that would have likely been known by many about a man that many in the state and country knew well in his time. He was Maryland’s Attorney General, Chief Judge of the 3rd District of Maryland, Associate Judge of the Court of Appeals, and then its Chief Judge starting in 1848. His name was Thomas Beale Dorsey. Complete information on him isn’t being listed here, because this isn’t meant to be another story to exalt him. This is a story about what he might have meant to a lot of people like me.

It’s generally said and known that in Maryland, the enslaved in the 1800s worked primarily with tobacco crops and then grains/agriculture, etc. The domestic sale and migration of slaves is also known about by many. The forced migration often led to the uprooting of men and women from their families, and any lives they were trying to build for themselves where they lived. Being “sold down the river” is a phrase with roots in the stories of forced migration of the enslaved from the North to the South, along the Mississippi River, to sugar and cotton plantations in the Lower South. There’s no shortage of material that exists about what some call the Slave Trail of Tears, as well as the difference in lifespan and living conditions between the enslaved on cotton and sugar plantations as opposed to those on Upper South plantations like Maryland’s. They were stark. “What does that have to do with Howard County and Mr. Thomas B. Dorsey?”, you ask?

A lot, it turns out.

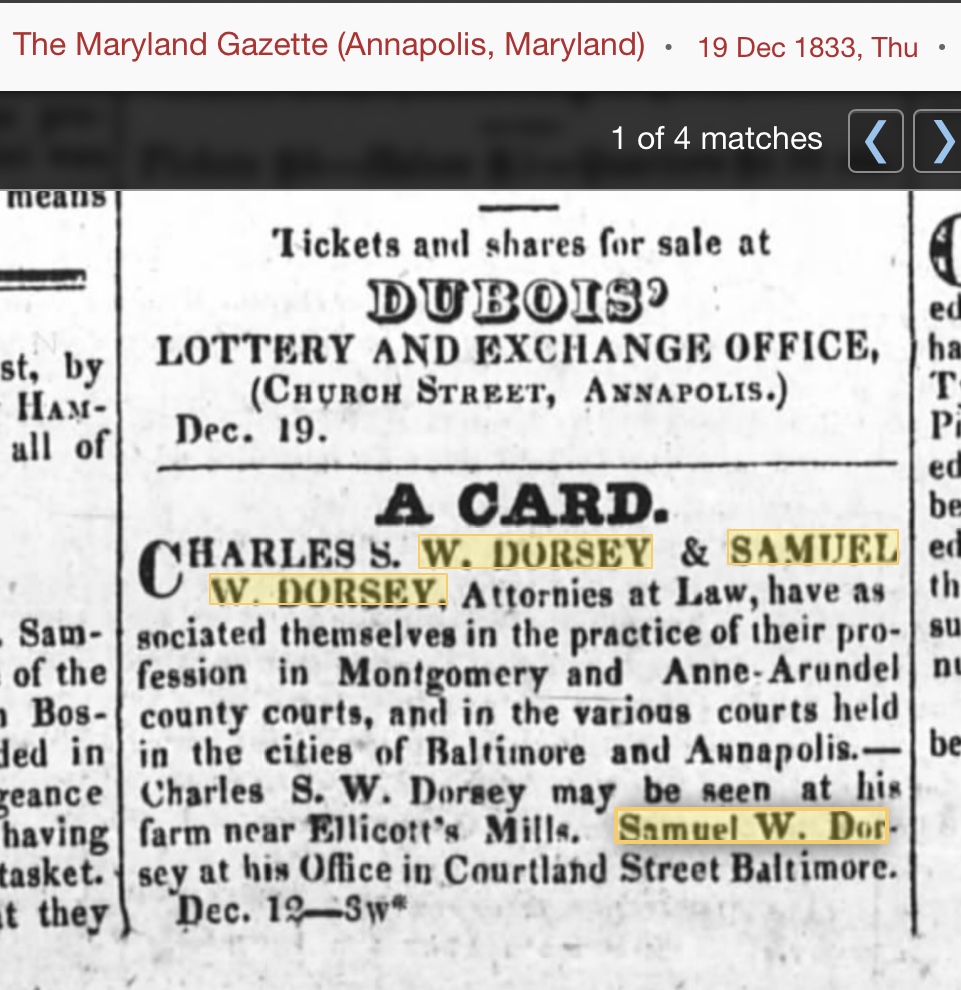

In 1833, Charles S.W. Dorsey and Samuel W. Dorsey were advertising for their joint Maryland law practice. Charles is believed to be the same Charles S. W. Dorsey who was Judge Thomas B. Dorsey’s brother. Samuel was the son of Judge Thomas B. Dorsey.

A few years later in early 1836, Samuel was advertising in a Mississippi newspaper that he opened up shop in Vicksburg, Mississippi. With a mixture of Miss./Louisiana and Maryland references such as Roger B. Taney (Chief Judge US Supreme Court), Ezekiel Chambers (Judge Dorsey’s co-worker at court), Stevenson Archer (also Judge Dorsey’s co-worker), and Philip E. Thomas (1st President of B&O Railroad), he was probably noticed by many in the Mississippi legal field.

Thomas B. Dorsey was married to his wife Milcah. Besides Samuel, there were 2 other sons of note for this story. John T.B. Dorsey was an attorney (he would become Howard County’s first State’s Attorney from 1851 to 1854). William H.G. Dorsey was also an attorney, and would become the County’s 2nd State’s Attorney after his brother’s term ended in 1854. Thomas and Milcah’s plantation home was called “Mount Hebron”.

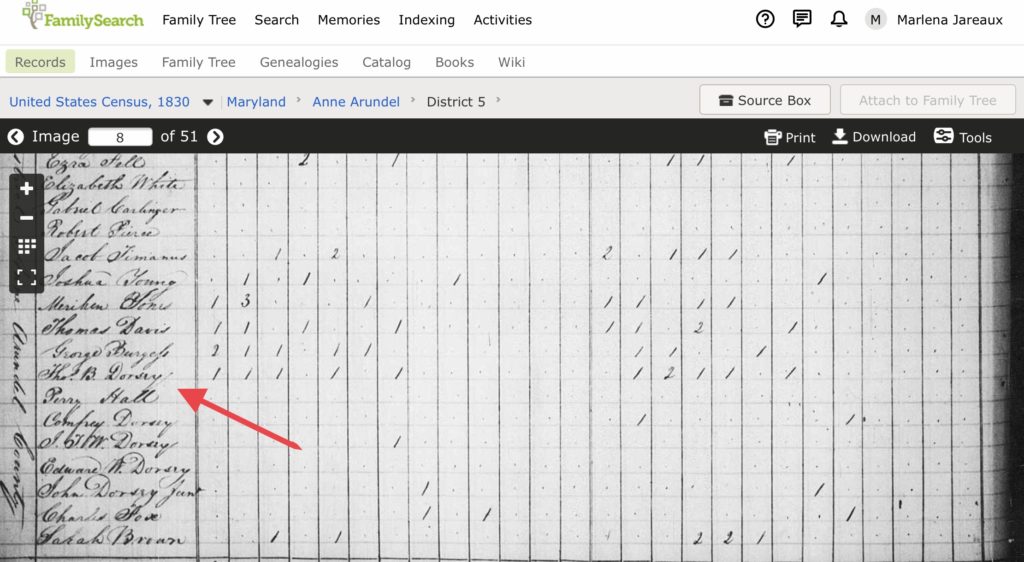

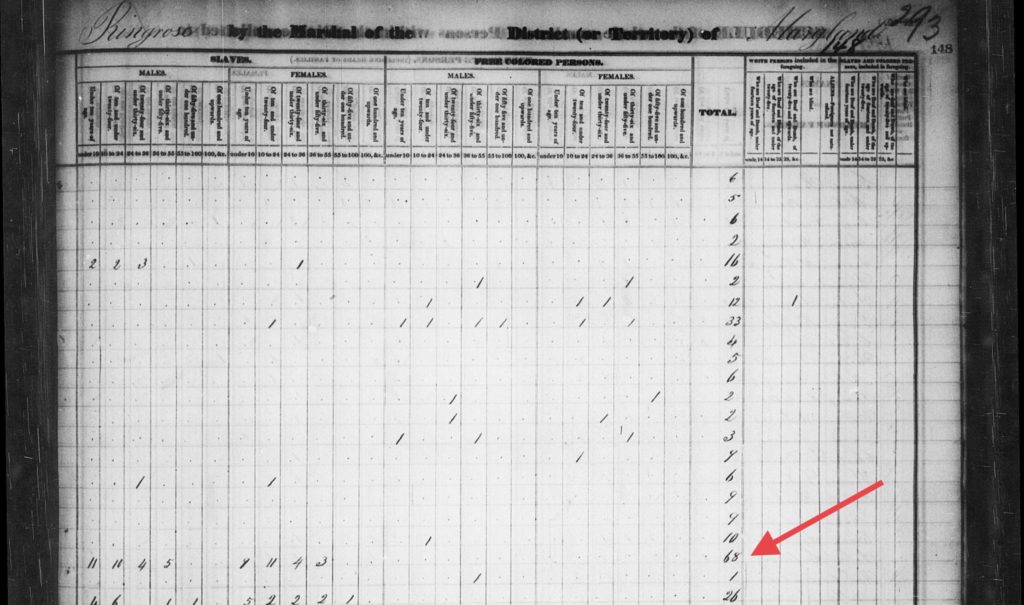

According to the 1830 census, Thomas and Milcah reported to be enslaving 57 people. (the total minus his family)

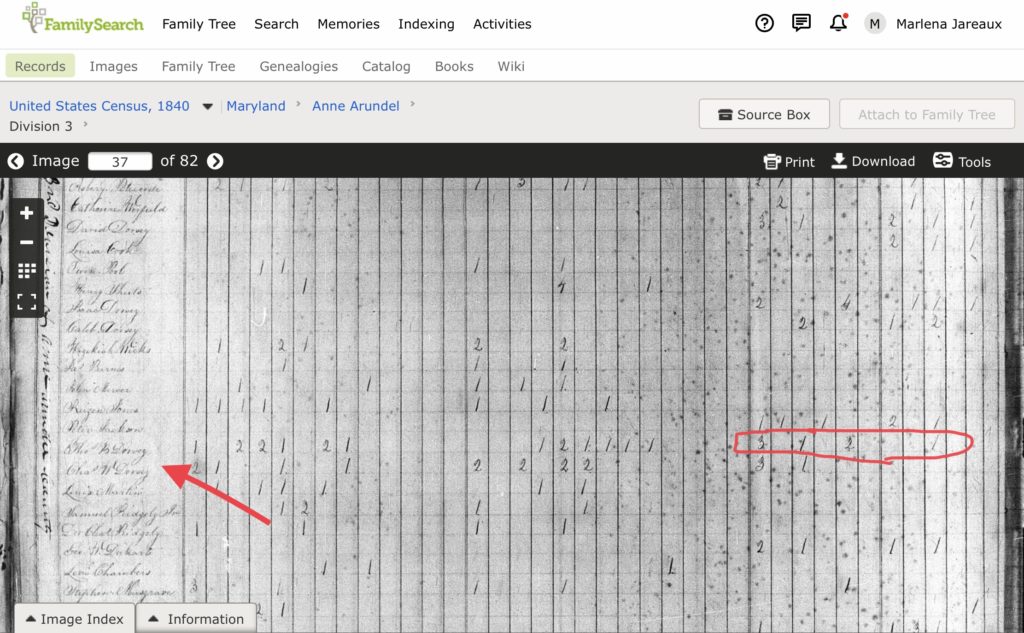

By the next census (1840), the numbers of enslaved reduced to 46. This may not be for the reason that you think. Yes, Dorsey did report having 7 free people of color residing on his property. No records have been located yet that explains the reasons why.

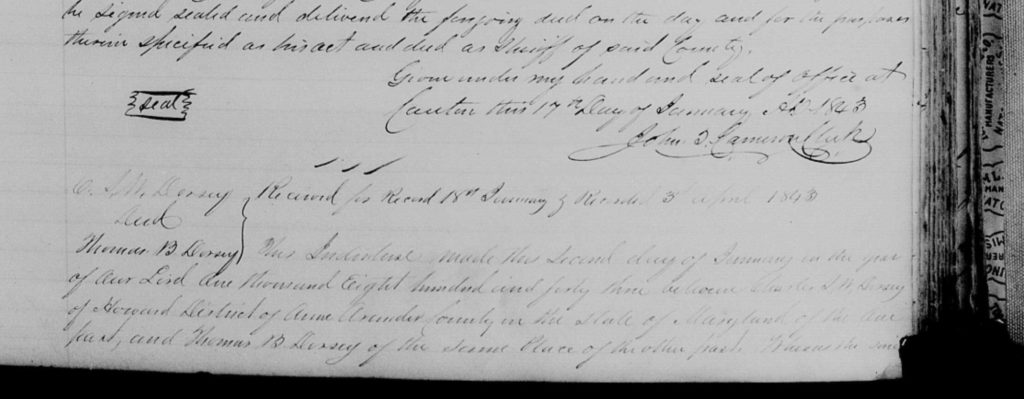

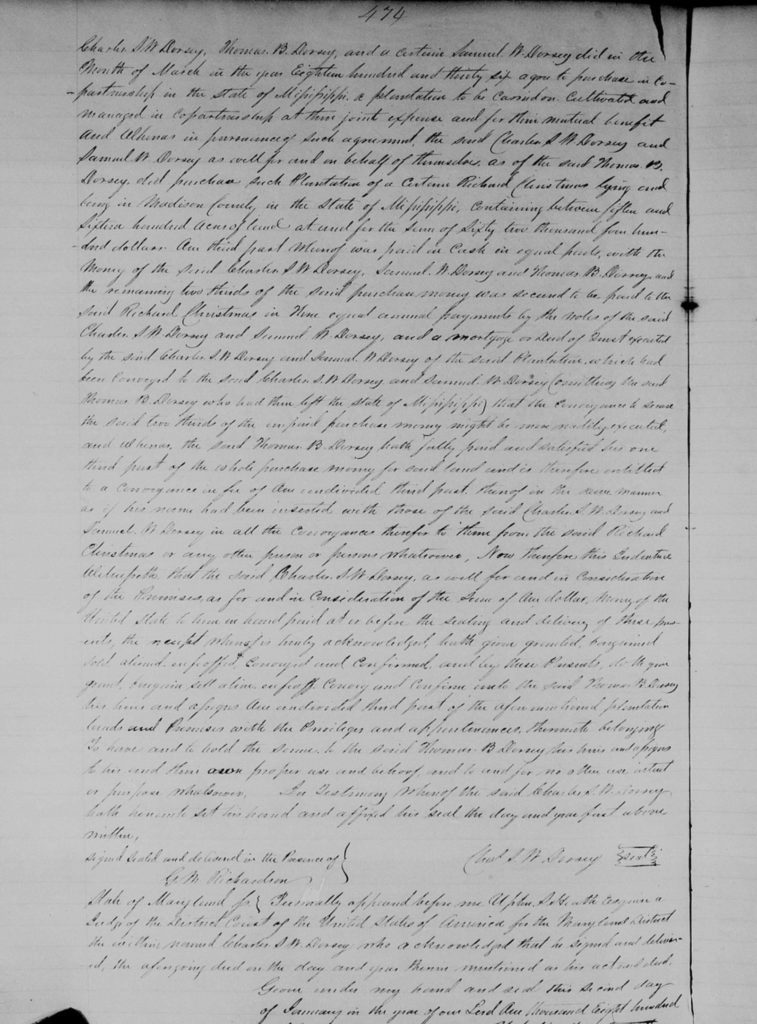

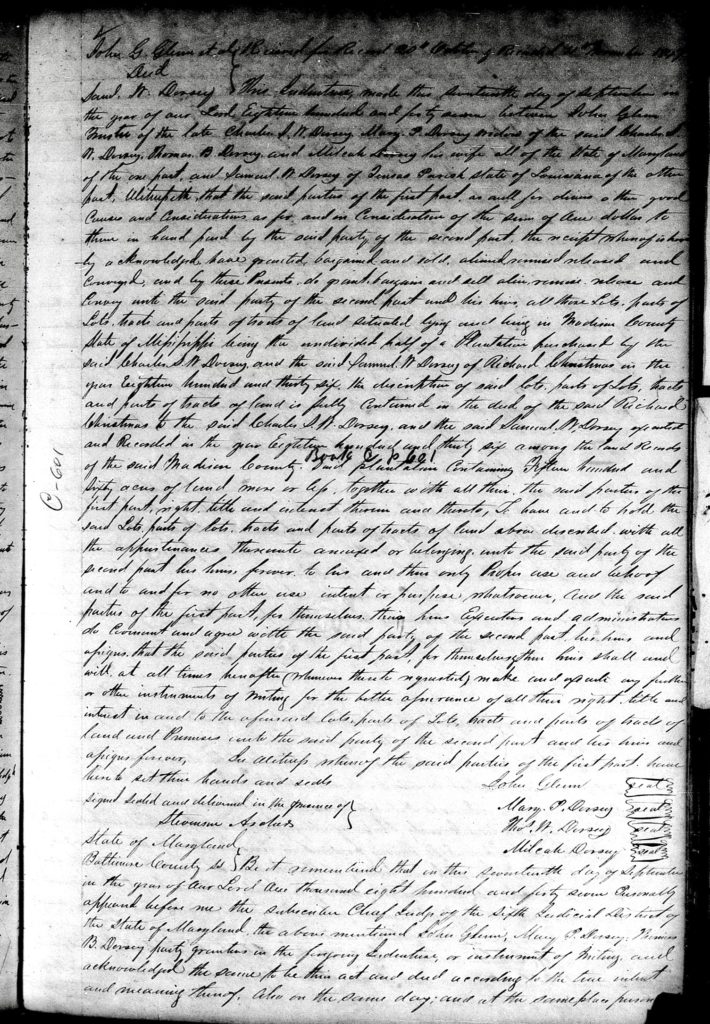

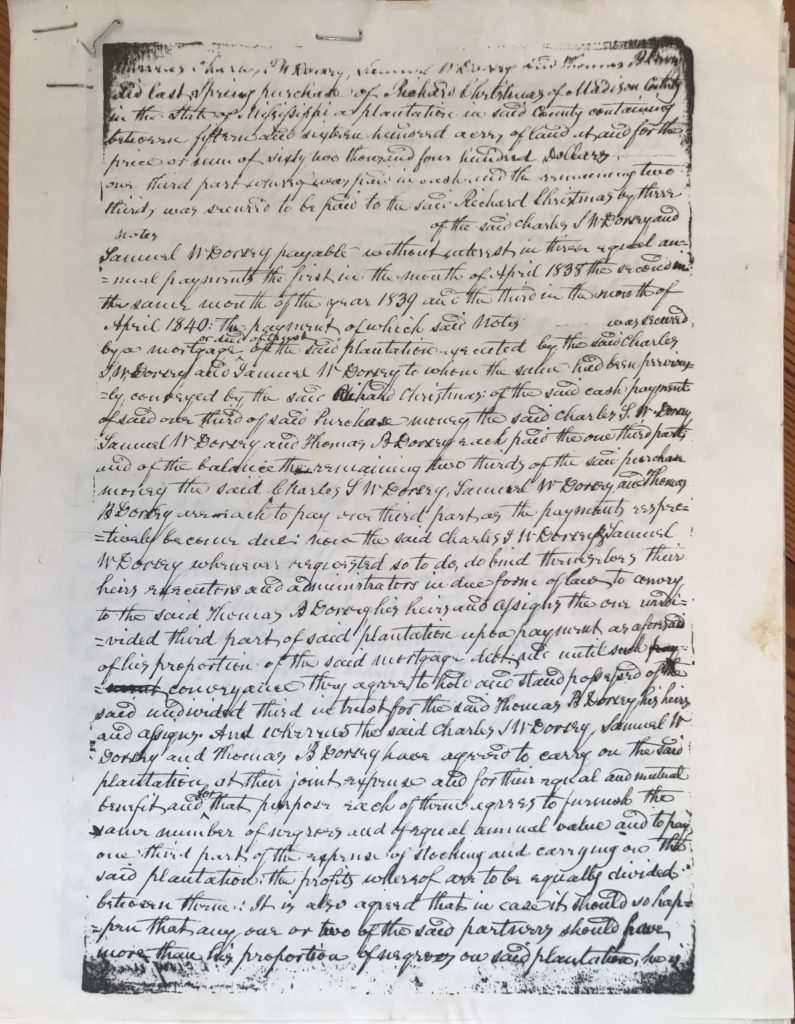

But, in between the 2 census takings in March of 1836, Charles, Thomas and his son Samuel purchased a large plantation in Madison County Mississippi for $62,400. It was between 1500-1600 acres in size, and was to be managed by them in a partnership arrangement.

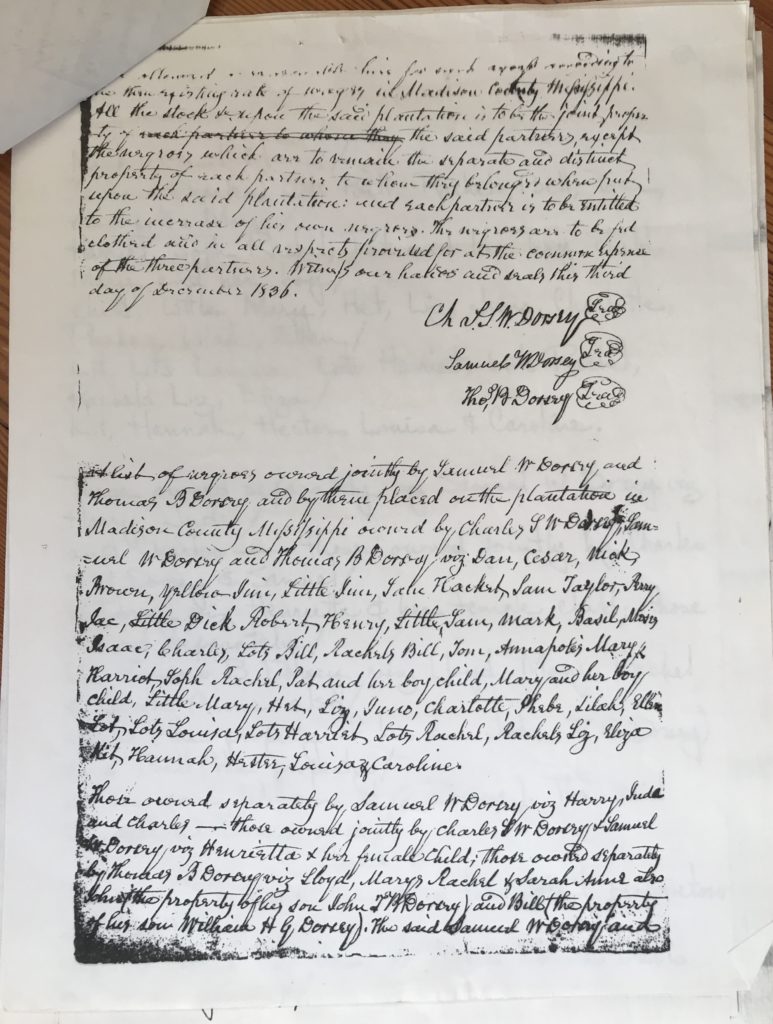

Along with jointly paying the mortgage for the plantation, each agreed to share in the joint expense of running the plantation for their equal and mutual benefit and profit. By written agreement between them dated December 3, 1836, they stipulated who among their enslaved would be sent to work at the Mississippi plantation. The list:

Enslaved jointly by the Judge and his son Samuel (co-owners):

| Dan | Yellow Jim |

| Cesar | Little Jim |

| Nick | Sam Hacket |

| Brown | Sam Taylor |

| Perry/Jac | Little Dick Robert |

| Henry | Little Sam |

| Mark | Basil |

| Moses Isaac | Charley |

| Lot’s Bill | Rachel’s Bill |

| Tom | Annapolis Mary |

| Harriet | Soph Rachel |

| Pat and boy child | Mary and boy child |

| Little Mary | Het |

| Liz | Juno |

| Charlotte | Phoebe |

| Lilah | Ellen |

| Lot | Lot’s Louisa |

| Lot’s Harriett | Lot’s Rachel |

| Rachel’s Liz | Eliza Kit |

| Hannah | Hester |

| Louisa | Caroline |

Enslaved by Samuel, individually:

| Harry | Juda |

| Charles |

Enslaved by Charles and Samuel, jointly:

Henrietta and her female child

Enslaved by the Judge, individually :

| Lloyd | Mary’s Rachel |

| Sarah Anne | Dick |

| Harry Collins |

“John” and “Bill”, enslaved by Thomas’ other sons, were also listed. The inventory went on to list others that had been hired from Allen Bowie Davis for 5 years. Allen was one of the judge’s son-in-laws. At least 26 others were listed in the document as being enslaved by Charles alone. It is entirely possible that some of them were actually his wife Mary’s, who was the daughter of Governor Charles Ridgely of the Hampton plantation in Baltimore County. She received an inheritance a few years earlier which included enslaved workers. Though Ridgely freed those he enslaved by his will, those outside the age of 25-45 for women and 28-45 for men were not immediately freed upon his death unless they were under 2 with a mother who had been freed.

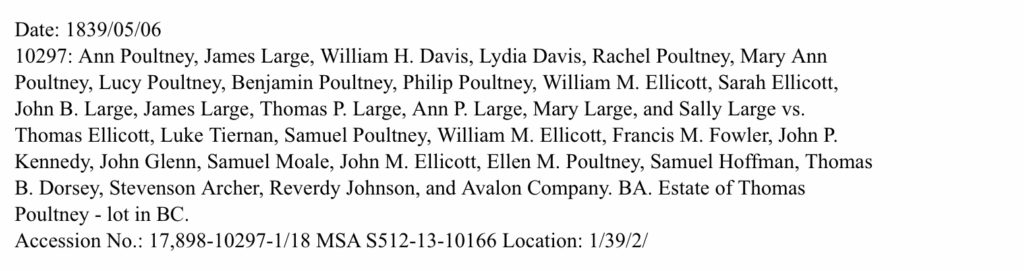

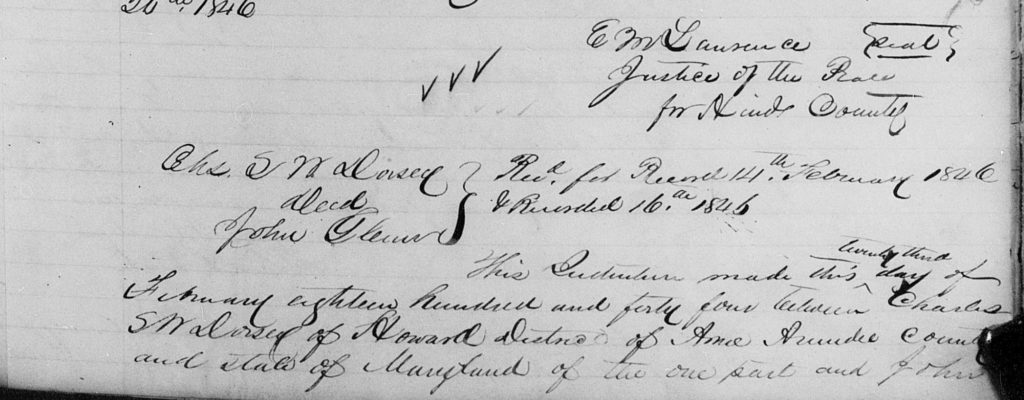

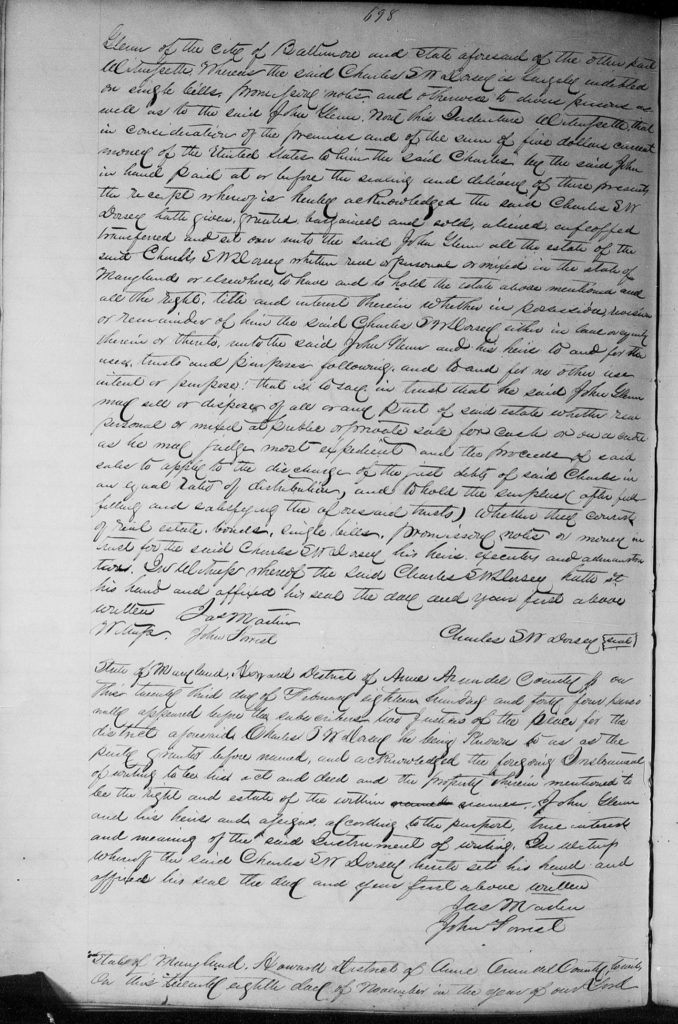

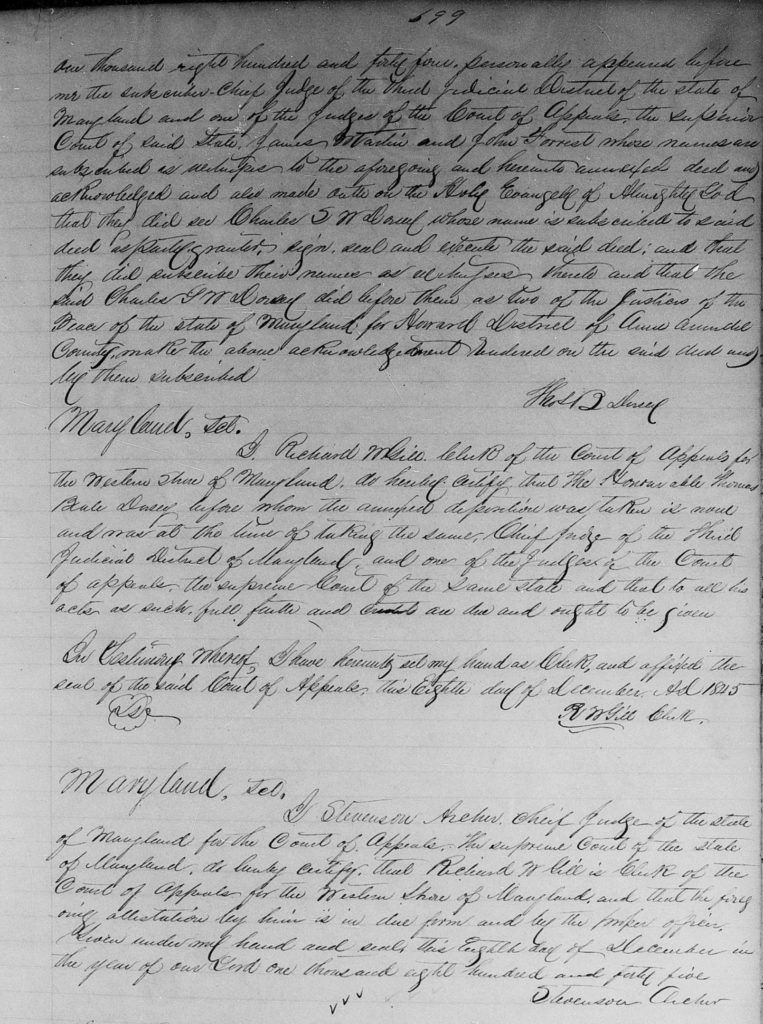

Prior to Charles SW Dorsey’s death, he transferred ownership of “..all of the estate.. whether real or personal or mixed in the state of Maryland or elsewhere..” to Baltimore businessman and attorney John Glenn. He owed Mr. Glenn money. Glenn, who would go on to be appointed a federal judge, was one of the men who were accused of financial misconduct and fraud in the Bank of Maryland fiasco that led to what is referred to as the Bank Riot of 1835 in which people lost millions of dollars in savings. Thomas Ellicott, who was affiliated with the start of the B&O Railroad, was also affiliated with Avalon which had been producing iron and tried unsuccessfully to compete with iron prices overseas for purposes of building the B&O. Ellicott was one of the purchasers of Dorsey’s Forge, its previous name before being changed to Avalon. The bank’s lawsuit against Ellicott for fraud was widely reported in the newspapers. A court declared Ellicott had to pay back the money.

Many of these same people were involved with each other in business, having invested in them together. Stevenson Archer was the Chief Judge of Maryland’s highest court right before Dorsey was.

Two years after Charles’ share of the plantation had been given to John Glenn, it was given to Samuel Dorsey for one dollar. That left the Judge and his son Samuel as the owners.

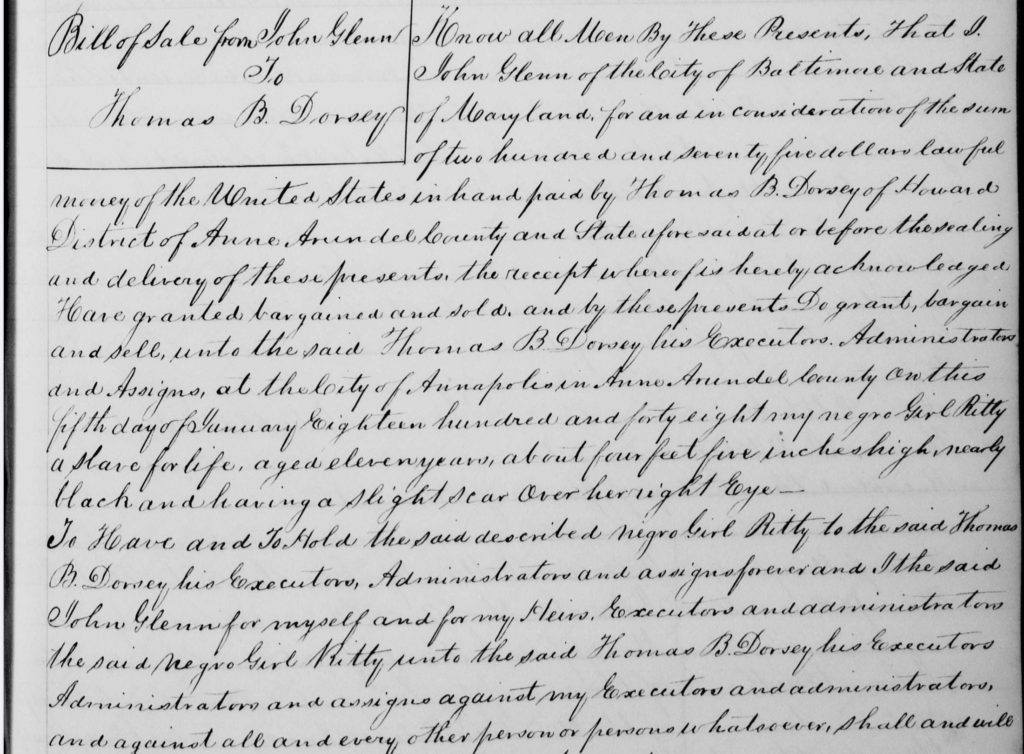

And a few years after that, Judge Dorsey bought an eleven year old girl named Ritty for $275 from John Glenn. She was sold as a “slave for life” to him that day in January 1848. He got named Chief Judge of the Maryland Court of Appeals in July of that year.

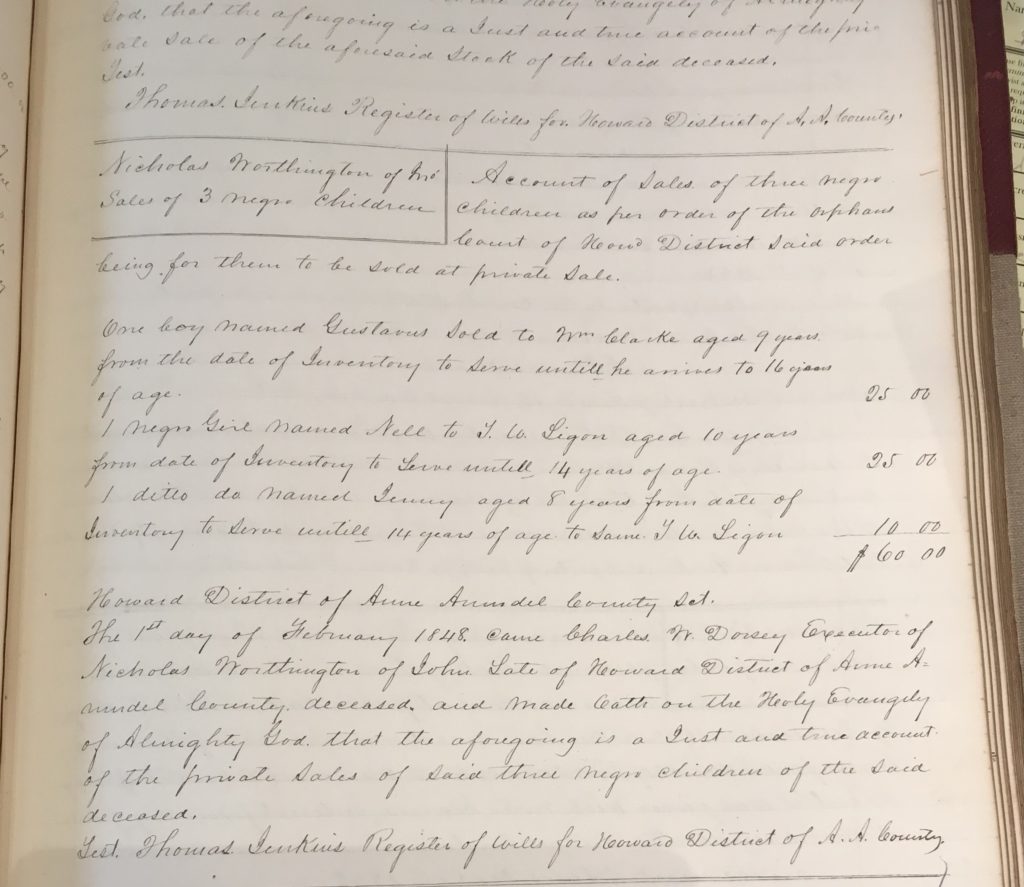

It was also the year that children were sold from Nicholas Worthington’s estate to Thomas Watkins Ligon, who was the area’s Representative in Congress at the time who went on to be Governor. His plantation was called “Chatham”, in Ellicott City.

Perhaps those men, women and children got sent down to Mississippi by boat or some other method. I don’t know if any of them ever came back to Maryland. This place made some big changes with some things. First it changed to being called Howard District. Many of the folks being discussed worked to change this place twice so that this place could be free from Anne Arundel county. It worked, and what first became the Howard District of Anne Arundel County became Howard County.

I also wanted to be free.

I already was free, so I didn’t think I had to try to run like my brother Sam did. But the people who decided to try to enslave me had power that my parents tried to fight against in court. I know about Thomas B. Dorsey because his son William was my dad’s lawyer, and the case was going to be decided in his court. I wondered about the people he made leave here to go to Mississippi, because I wondered if he was going to be able to see past my black skin to see me as more than property to be bought, sold and dispatched in ways designed to increase HIS family’s inter-generational wealth. The people who took me from my parents didn’t think I was different. I hate thinking I’m different than Sam or those Mississippi folks, because to me…I’m not. But I’m forced to by these people, and the laws we had no hand in creating that make me.

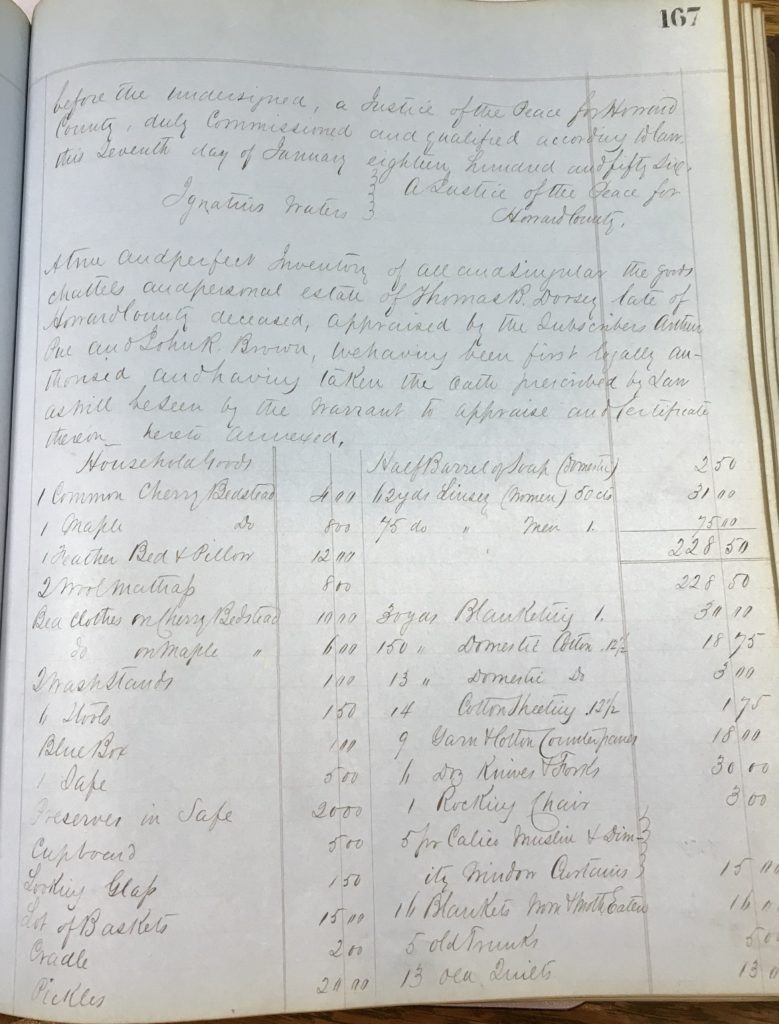

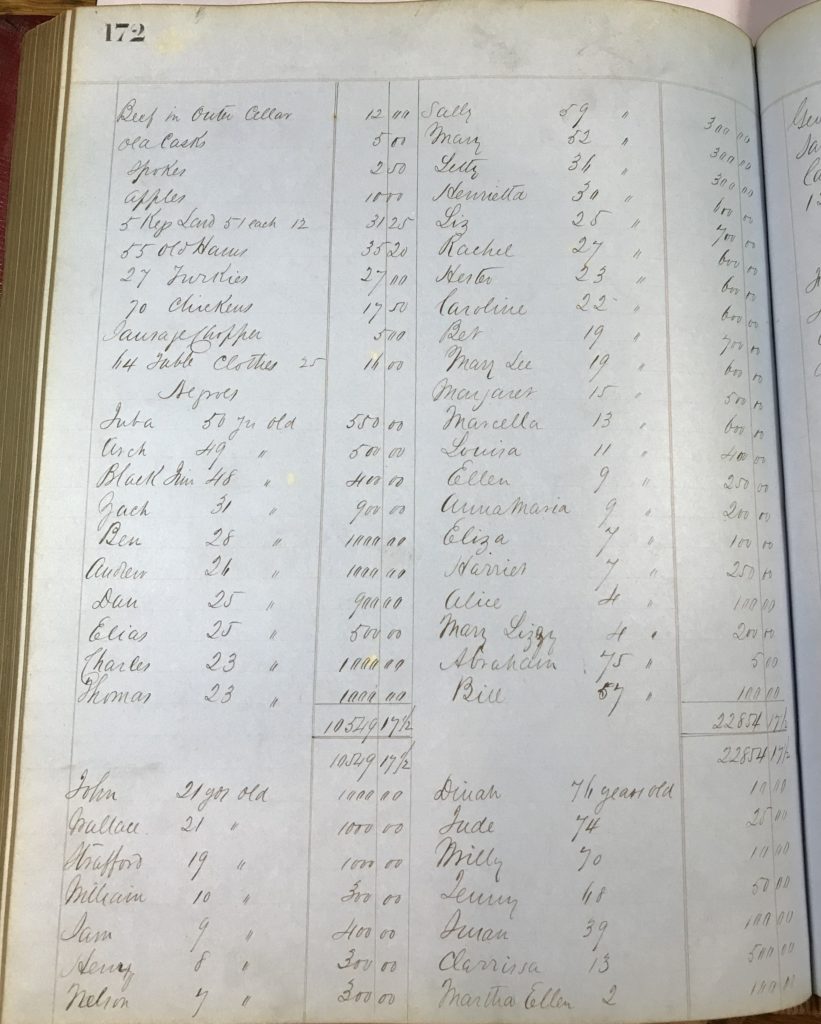

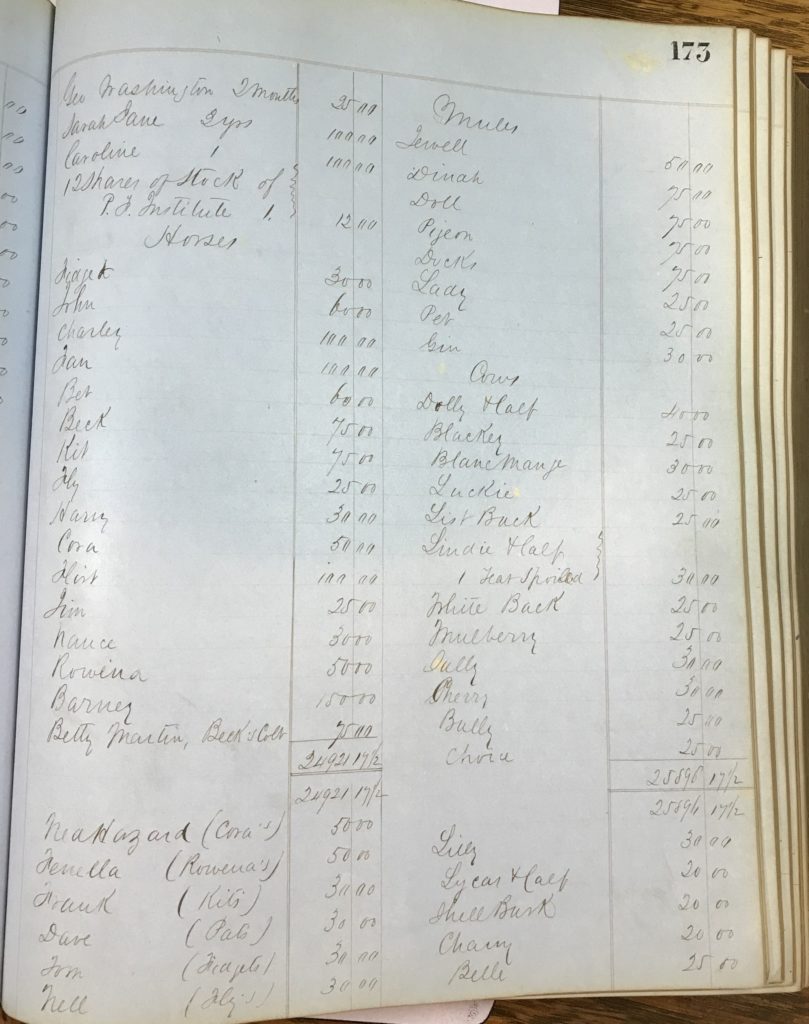

Judge Dorsey died at the end of 1855, some time after a disappointing but somewhat predictable outcome for my family in the court that his family of attorneys regarded with great honor and respect. It wasn’t a complete loss for me, you’ll read one day in the book. Judge Dorsey died reportedly enslaving almost 50 men, women and children, according to the initial report given to the Howard County court after his death. It is hard for me to decide if I think he saw me as a person since he had died owning a mule named Dinah and a 76 year old woman named the same. The men assigned by the orphan’s court to place a value on everything he owned said the woman was worth $10 and the mule $75. Men of their time.

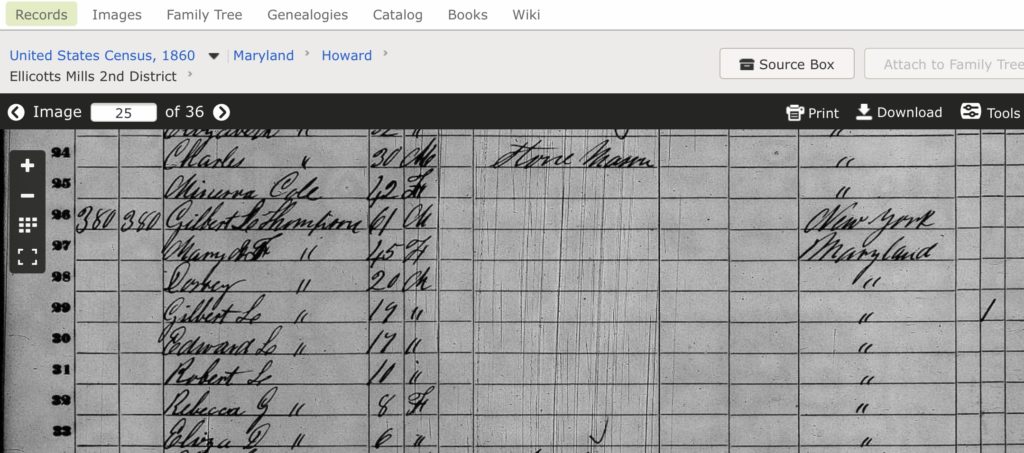

The judge’s grandkids were to receive negroes or mulattos upon his death, with the exception of Benjamin Harrison Dorsey who got a colt. They were:

Dorsey Thompson, Mary’s first-born who was about 16 years old, was to receive Henrietta (age 30) and her son William (age 10).

Gilbert L. Thompson, who was about 15, was to receive Margaret (also age 15) and Eliza Jane (age 7)

Edward L. Thompson, who was about 13, was to receive Harry and Anne (age 9), daughter of Dinah

Robert L. Thompson, who was about 7, was to receive Louiza (age 11), who was also Dinah’s daughter

Rebecca G. Thompson, who was about 4, was to receive Alice, also Dinah’s daughter

Thomas B. Dorsey, son of John T.B. Dorsey, who was about 6, was to receive Sam (age 9) and his sister Harriet (age 7)

Since none of their last names are listed in the judge’s will or inventory, I’m not going to be able to tell you much about them now, and I’ve done my best to match them with the will.

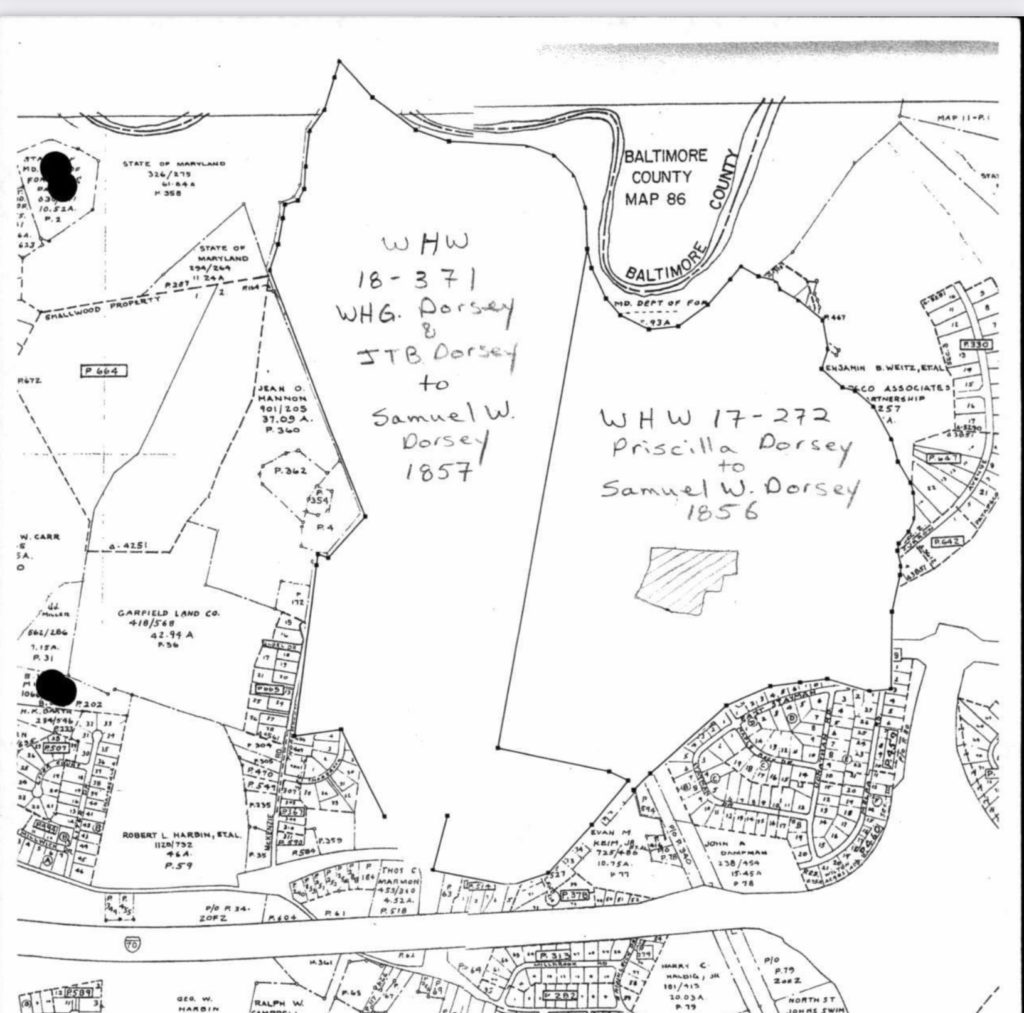

Thomas B. Dorsey’s residence in Howard County was known as Mount Hebron, and it was a massive estate of more than 2100 acres. Not bad for what started out as a wedding present from his father. I understand that the judge died owning 269 bottles of wine. 900 acres of “Hebron” was to be split between 3 of his surviving children named in his will. The rest was to be sold. For some reason, John T.B. Dorsey wasn’t given land (he had other property already), and Samuel had already been given “much” according to his dad. (Probably, because of Mississippi). Samuel would end up buying much of the land after all from the estate, and then selling it to John T.B. Dorsey. Here, you can see the sizes of just the 2 pieces of land that got sold to Samuel and then to John T.B. Dorsey, placed over top of a more current map so you can see how it compared to current land lot sizes. Part of the land is now owned privately, some is owned by a Presbyterian Church. Mount Hebron High School derives its name from it.

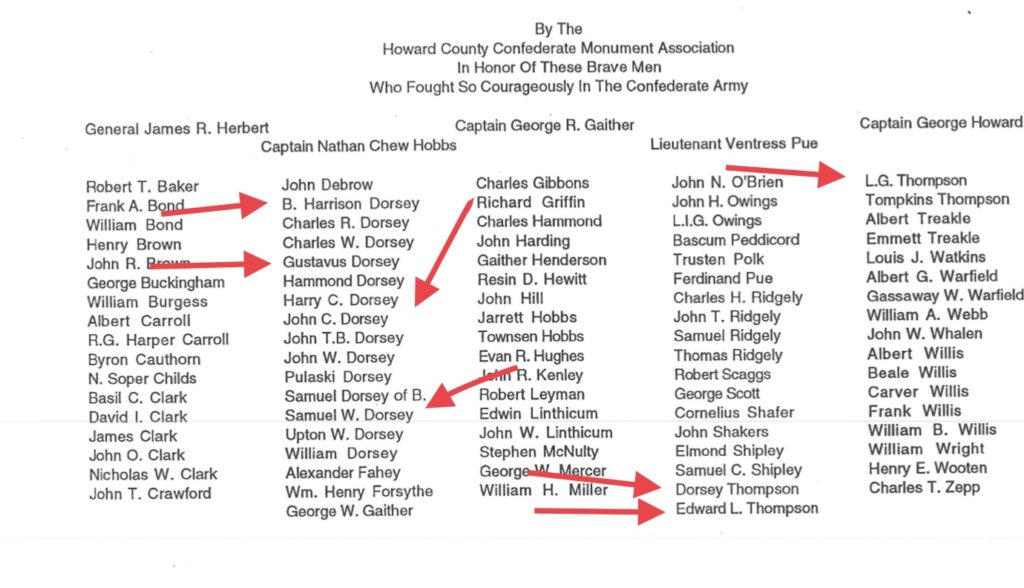

There are other things that can be said regarding the Dorseys and Thompsons. The Civil War changed things in many places of the country. My brothers fought in the US Colored Troops, while John T.B. Dorsey fought for the Confederacy along with other members of Judge Dorsey’s family. A monument was made for the confederate men and placed at the public courthouse, but not for my brothers nor my husband who fought for the Union. Many of the Thompsons listed on it were the children of Mary Thompson (the judge’s daughter). Dorsey Thompson was the judge’s grandson. So were Edward and Gilbert. (I think the monument has “LG” instead of “GL” Livingston).

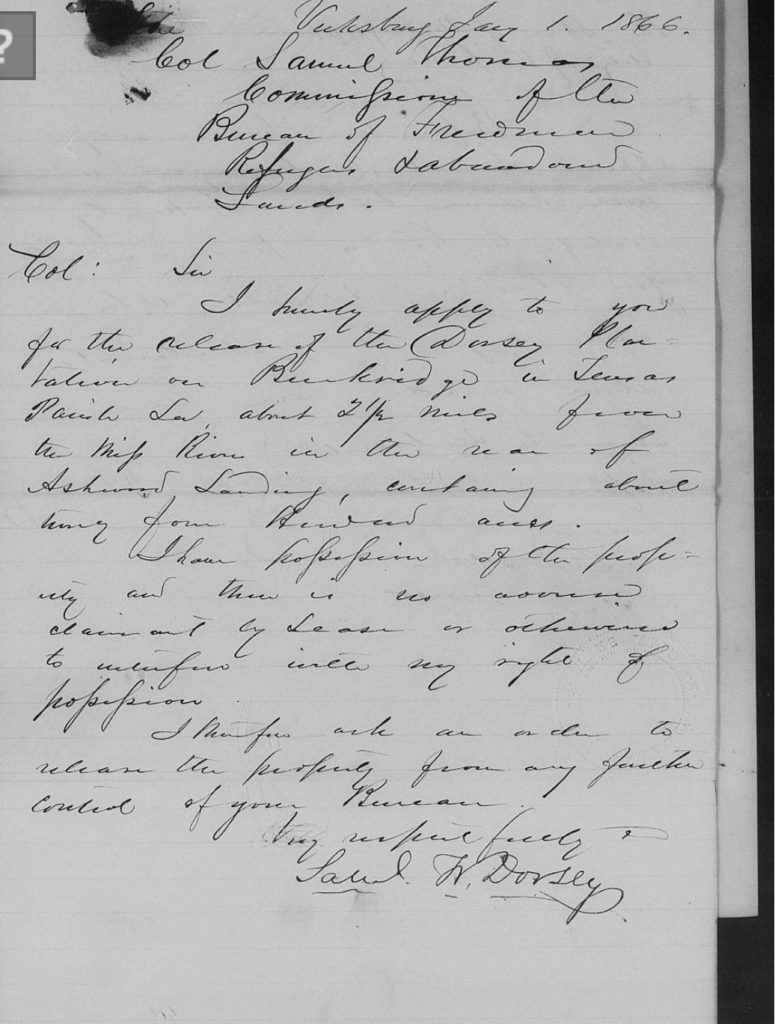

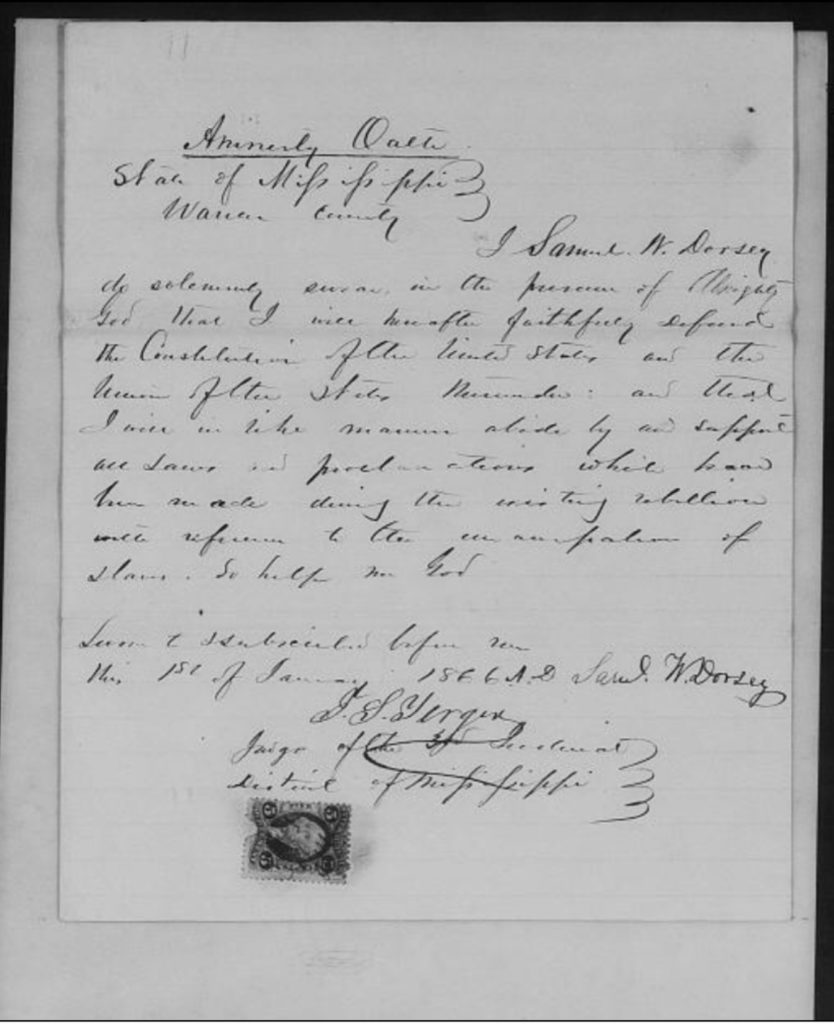

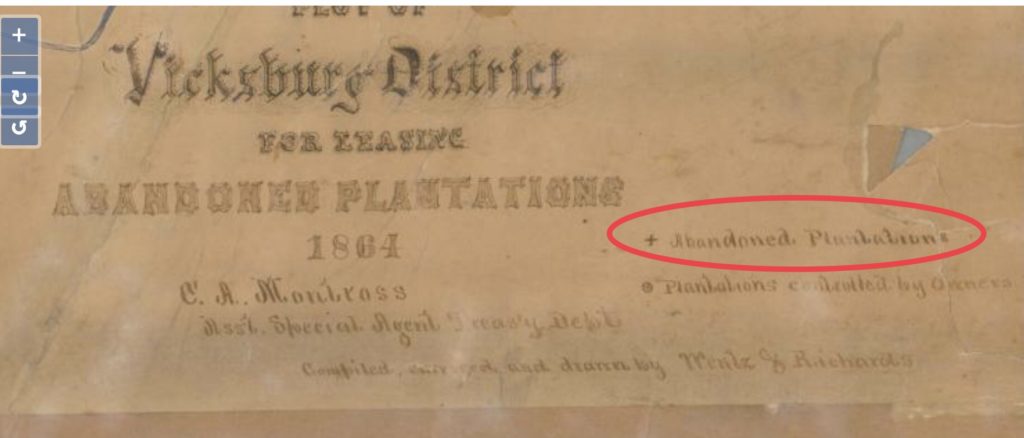

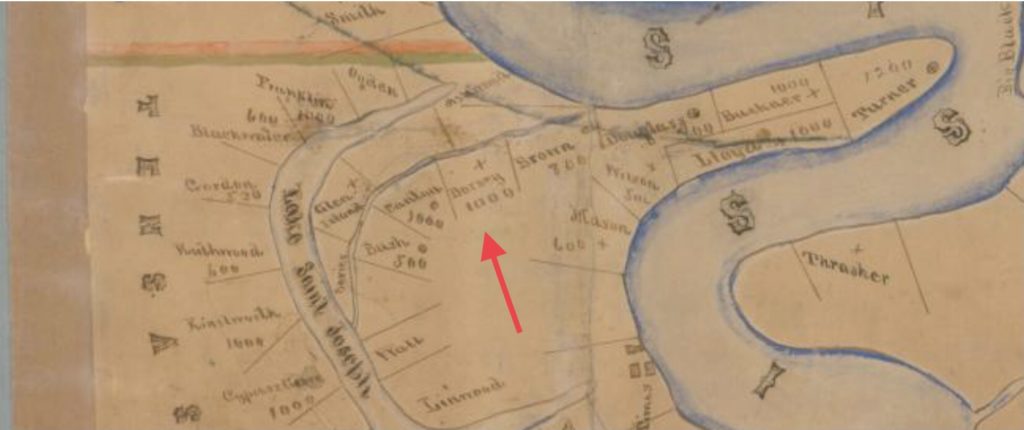

After the war, Samuel Dorsey had to spend time trying to reclaim his land in Louisiana from the Freedmen’s Bureau. He apparently abandoned it. Here is his petition, along with an amnesty oath he had to take regarding him defending the Constitution and abiding by laws made regarding the emancipation of slaves.

This was his land:

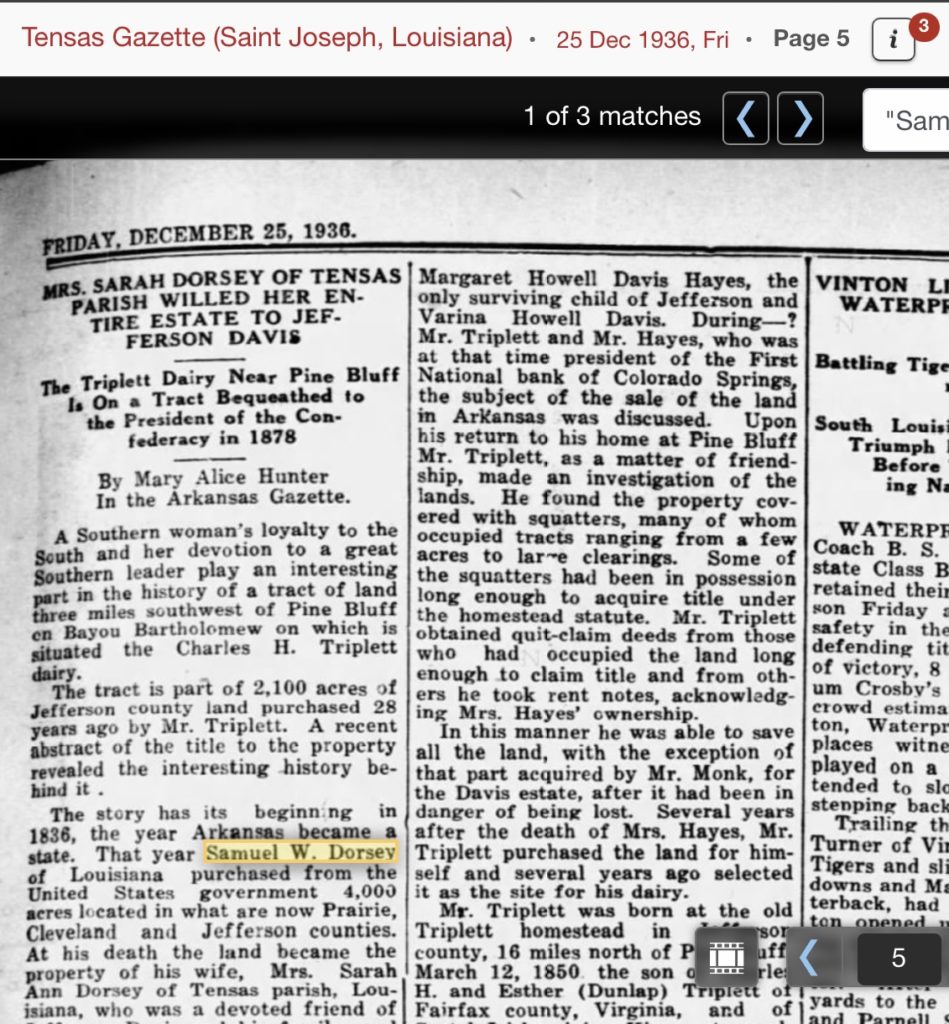

Samuel died in 1875. I was still living in Howard County at that time, with my husband and my children, but would move a few years later. If this Wikipedia article is accurate about him, it was a cotton plantation he had and he died from the Mississippi River overflowing. He had been involved in Louisiana having seceded from the Union. That’s definitely accurate.

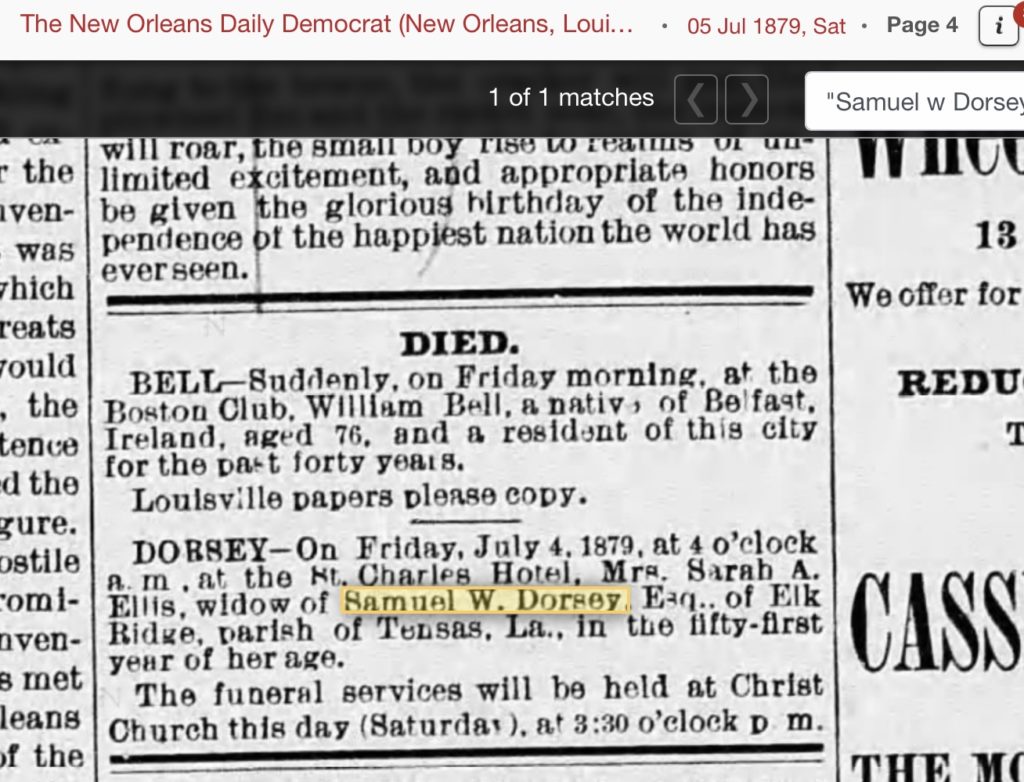

His wife, Sarah Ellis, an author, would became known for something she wrote before she died.

HER WILL!

SHE LEFT ALL OF HER RESIDENCES AND ESTATE TO JEFFERSON DAVIS,

PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERACY!!!

They called their Louisiana plantation “Elk Ridge”!

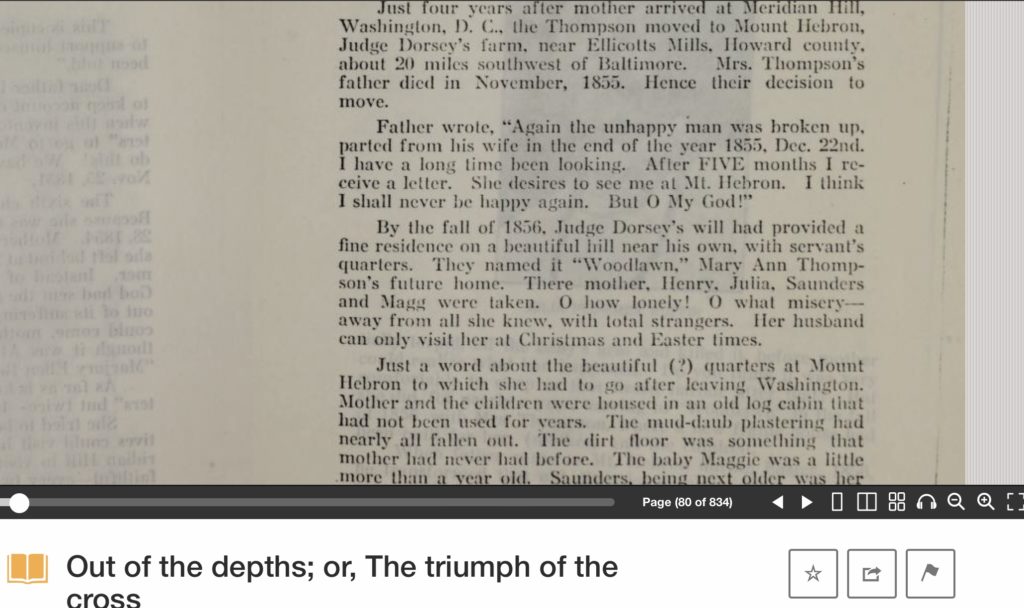

I can’t give everything away here about John T.B. Dorsey, because it’s in the book. Others have written about his sister, Mary. She was married to Col Gilbert Thompson, and they moved to Mount Hebron for a time after her father died. Then they moved to Woodlawn.

This is the property. When it mentions Rebecca and John Rogers (it was Judge Rogers), it’s the Rebecca who was 8 in 1860 living with her parents.

https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Howard/HO-48.pdf

Much is known about living conditions with them at Hebron, and then Woodlawn, from at least one of their enslaved, courtesy of the diary of Adam Plummer. He had been traveling back and forth from where he was enslaved in PG County, to see his wife Emily and their children. We know her:

Emily Saunders Plummer:

https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshall/html/plummer.html

This is from one page of the book written by their daughter, mentioning Mount Hebron:

Adam Plummer’s original diary:

https://anacostia.si.edu/exhibits/Plummer/Docs/PlummerMSS_FastWeb.pdf

Beulah Buckner’s papers regarding Judge Dorsey’s Mississippi enterprise:

More on Slavery’s Trail of Tears:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/slavery-trail-of-tears-180956968/

More about cotton plantations:

Wayland Seminary in DC, previously Meridian where Judge Dorsey’s daughter Mary resided with her husband Gilbert Thompson before moving to Mount Hebron after his death: